Greek Festivals

Even After Decades, Immigrants Affect our City

v i s u a l i z i n g i m m i g r a n t P h o e n i x

Cynthia Canez

October 2016

We often assume that the impact immigrants make upon our city ends with the generation that migrated to the United States. But subsequent generations may carry on traditions that continue to link them to the homeland of their forebears. The new generations of children and grandchildren from Greek immigrants that migrated in the early 1900’s are a good example. These descendants of immigrants will often appear completely assimilated to the American way of life, and in most aspects, that is true. They speak the most prevalent language (English), know the culture and participate in American traditions: all activities that would give the sense that they come from an all-American family. This appearance of assimilation is of course facilitated by their being white Euro-ethnics. But a closer look reveals that bits of their ancestral homeland’s Greek culture, brought to the US by their immigrant family members, may be intertwined with their practice of American culture, to create a beautiful blend of traditions. I had the pleasure of experiencing the blend of Greek and American cultures when I made field trips to A Taste of Greece and Greater Phoenix Greek Festival.

The majority of Greeks who settled in the US migrated during the last great wave of European migration in 1880—1920. This is shown by the graph. Although there is still a small but steady flow of Greek migrants every year, the majority of the immigrants that migrated have already established their own families in America for the last two or three generations (If you want to learn a bit more on Greek migration check out this article). That being said, descendants of Greek immigrant families make an excellent case study of the lasting effects of migration within their families. What is a better place to observe a specific culture than a festival celebrating it?

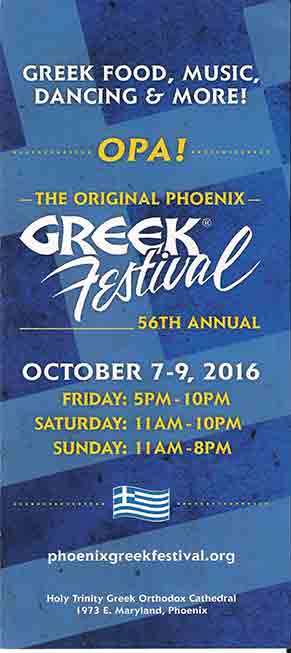

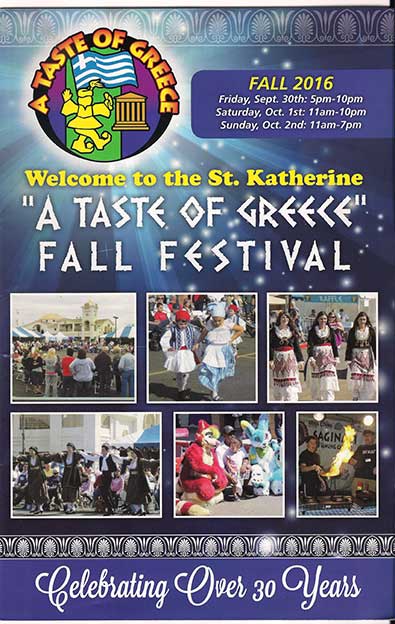

A Taste of Greece and Greater Phoenix Greek Festival were very similar. They had the same vendors plus or minus a few, the same types of food and entertainment. The only difference was the size of each festival and the number of people that showed up. Therefore, I will combine this discussion of my experiences at the two festivals, and touch on the importance of the main aspects they shared.

Right off the bat, both festivals were held at Greek Orthodox churches, which in itself is an excellent example of the effects of immigration. Greek Orthodox Christianity was brought over by immigrants decades ago, as stated on Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church’s website. Gradually the demand grew with the number of immigrants rising to build multiple churches to fit their needs. The scattering of Greek Orthodox churches throughout metro Phoenix is an indicator that the religion stuck around, even growing in population, and continues to be practiced today by immigrants themselves and their descendants. Both churches are built in the architectural style of iconic churches in Greece. The typical look is multiple domes, often colorful, with crosses standing on top. As you can see the right picture is of blue domed churches in Oia Santorini, Greece, one of the most popular tourism places in the Greek islands. The left picture I took of St. Katherine’s Greek Orthodox Church in Chandler. Both churches are constructed with the same style in mind, but St. Katherine’s is built to “fit in” with typical Arizona architecture, with its red shingled rooftop. That small but significant difference shows a mixture or synchretism taking something of Greek culture and mixing it with American culture.

The first thing I noticed was the food booths, probably the most visited area of the festival. Immediately upon steeping through the gate leading into the back lot of the church, the enticing aroma of cheese, honey, and lamb filled the air. Walking through the booths I noticed a great number of dishes that I hadn’t heard of before, such as sagnaki, a fried cheese ball, and loukoumades, deep fried flour balls drenched in honey and a cinnamon sugar sprinkle. At each festival, a large dining hall served either a chicken or lamb dinner, served with rice and a pastry. As noted, most of these dishes contain either meat or cheese. Later, I was surprised when I talked to the priest of Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Cathedral, who told me that followers of their religion eat a plant based diet, excluding all animal products, for around 200 days of the year. The foods that were seen at the festival were considered special in the sense that they could not be eaten all the time. The pictures below are off some of the booths at the festival as well as some of the Greek foods that I tried.

The biggest and most important part of each festival was the entertainment tent. Both A Taste of Greece and the Greater Phoenix Greek Festival had a large tent set up in the center of the lot, with seating facing the center circle where dancers would perform. I walked up to the tent right as the dancers were about to perform. This particular piece was performed by the high school and college level dancers, dressed in traditional Greek outfits. As the dancers were poised at the ready, I noticed that the group members wore a few different types of traditional costumes all coming from different islands of Greece. Most notably the girls wore either a red or green beaded head scarf, with blue, a green or red embroidered dress. The same colors showed up in the guys’ outfits where they wore either a blue or red vest with dress pants. A musician started to play the music, and all of a sudden the atmosphere of the tent changed. As the dancing started people started to clap along, and shouts of “Opa!” came from different directions. Audience members started to run up to the dancers to shower them with dollar bills. It was unlike anything I had ever seen, and I felt as if I was going to tear up watching this large group of people celebrate their heritage. (see videos below)

I was able to talk to one of the dancers after the performance for a short while. She explained that the dancers all were organized by the church, and followed the Greek Orthodox religion. She started dancing with the group with she was younger and grew up doing it.

I was also able to see two groups of kids perform, one group was the under five-year-old age group and the other a six-to-twelve age group. It was interesting to see that young kids in the church start off learning the traditional dances Greek culture and age together as the years go on, carrying on the traditions.

Last but not least, was the abundance of vendors selling goods at booths sprinkled around the festivals. There are two in particular that I will touch on, one being a booth that sold jewelry, and another that sold T-shirts. Although these booths don’t sound very special, what they sold is an important indicator of who is attending the festival and their heritage.

First the jewelry booth was selling not only trendy American style jewelry, but also jewelry with Greek and eastern European symbols. The most recognizable symbol displayed was the Hamsa, an open right hand with the evil eye in the palm. This symbol is mostly seen in the Middle East and eastern Europe, Greece included, as a protection symbol from evil spirits and sickness. It is also used as a symbol of strength and blessings. The prominent use of this symbol in the jewelry sold at this event shows that a belief centered in eastern Europe has traveled with immigrants to the United States and is still held by the families today (NCUIRE team member Ileen Younan also discovered these evil eye amulets in a Mexican Mercado in Phoenix; these artifacts were carried to many cultures along the global currents of empire and migration).

The T-shirt booth on the other hand directly reveals the major group of people that attend these festivals. As you can see from the photo, the sayings on the shirts are aimed not only at Greek immigrants, such as the “100% Greek” shirt, but also for children of immigrants that were born in America, such as the “made in America with Greek parts” shirt. This shows that an identification with the Greek culture still exists after generations of American born descendants. The priest I spoke with at Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Cathedral said that depending on the day and time of the service, he will either speak Greek or English. For example, most weekday nights he will do the service in Greek because mostly older individuals and immigrants go then, and on weekends he will speak English because that is when most Greek American families go to service. The change in languages is also an indicator that as new generations are formed, the heritage and culture are retained.

As you can see, there might not be a lot of Greek immigrants migrating now, but they continue to have a lasting effect on our community. The heritage and culture that migrants have brought to America can be seen in the many of generations of their descendants that still practice traditional Greek dancing, cooking, and religion. Although it may be subtle, traces of Greek culture can be found in the city itself, most notably in the Greek Orthodox churches scattered throughout the valley. It goes to show that if we look for the impact of other migrant diaspora communities through similarly subtle means, we are likely to find its evidence throughout the city.